The Evolution of the Alphabet

From Egyptian Hieroglyphs through the Aramaic, Hebrew, and Arabic alphabets. And my own secret alphabet, just for fun.

My wife and I recently returned from our honeymoon to Israel and Jordan! During our trip, we thought it would be fun to learn both the Hebrew and Arabic alphabets.

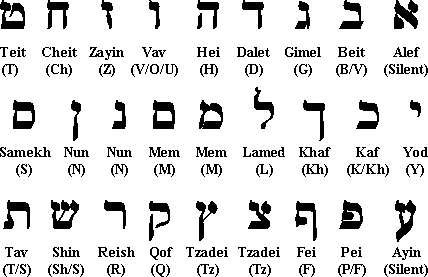

On the surface, these two scripts appear totally different. Here’s the Hebrew Alphabet:

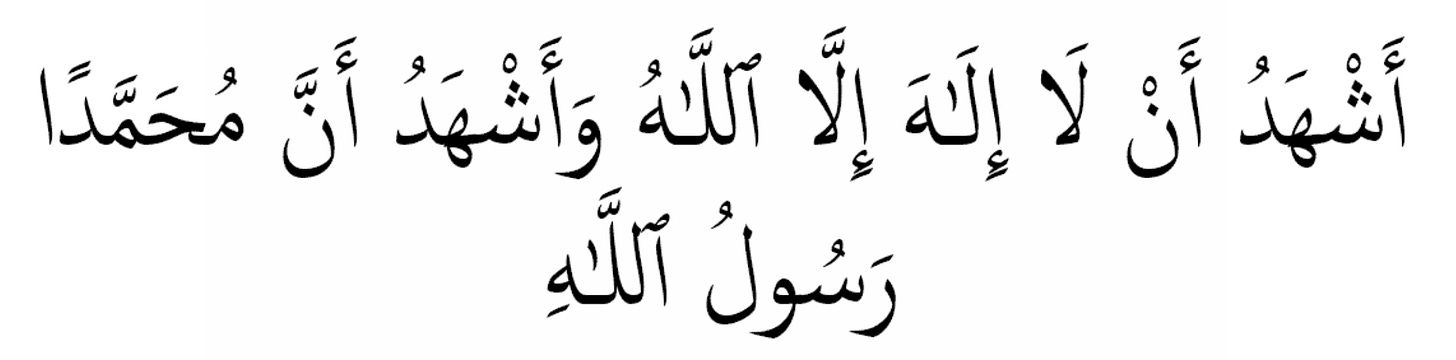

And here’s the Arabic Alphabet.

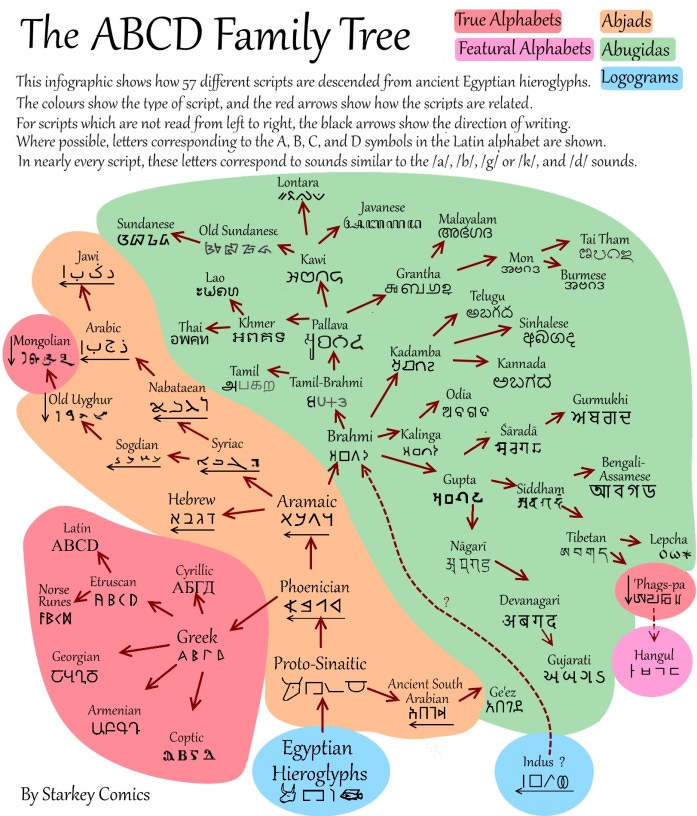

But in fact, these scripts are very closely related. Alphabets, just like languages or species, are related by a family tree.

Before we get to that though, we have to define what we mean by “alphabet.”

Types of Alphabets

Strictly speaking, Arabic and Hebrew are not “true” alphabets, despite the Hebrew alphabet being named “alef-bet.” Instead, they are “abjads,” a word derived from the first four letters of the Arabic alphabet, which refers to alphabets that lack separate symbols for vowels. In Hebrew and Arabic, as in most Semitic scripts, only the consonants of words are written, and the vowels are implied.

Abjad: A set of symbols representing consonants that define the basic sounds of a language. Examples: Arabic, Hebrew, Aramaic

Alphabet: A set of symbols representing consonants and vowels that define the basic sounds. Examples: Greek, Latin, Hangul (Korean).

Syllabary: A set of symbols representing syllables as the basic phonemic unit in a language. Examples: Hiragana (Japanese), Cherokee, Linear B.

Abugida: A set of symbols where consonant symbols are modified with vowel diacritical marks, falling somewhere between a syllabary and an alphabet. Examples: Devanagari (Sanskrit/Hindi), Thai, Khmer

Logograms: A set of symbols, each of which represents an entire word or concept. Examples: Chinese, Mayan (also has some syllabic glyphs), Egyptian (sort of)

Complexity Tradeoffs and the Invention of the Alphabet

You can classify these different writing systems by how many symbols are necessary to encode a full language:

Logographic Script

Fully logographic scripts, like Chinese, need upwards of a few thousand (Chinese has 50,000 in total, but only ~2,000 necessary for everyday life). A true logographic script is, at least in principle, entirely decoupled from the sound of the language, encoding only the meaning. That’s why the hieroglyph for “sun” is comprehensible even to people who don’t speak Ancient Egyptian.

Here’s another example. I know you don’t speak Ancient Egyptian, but I’ll bet good money you know what this glyph means anyway:

This is a huge advantage in certain contexts. For example, despite many non-mutually-intelligible dialects of Chinese coexisting in China today, they can all use the same standardized Chinese script, with no pesky spelling and pronunciation issues to impede understanding. Useful!

Syllabaries

Now, a syllabary like Hiragana or Cherokee reduces the enormous cognitive barrier of memorizing thousands of characters, needing 50-100 to encode the language. It’s also a very natural way to break down a language — instead of encoding its meaning, encode its sound (which in turn encodes its meaning), and the syllable is the most obvious basic unit of sound. However, you’ve fundamentally changed the writing system to encode sound, not meaning. Thus, you’ve moved the cognitive load from memorizing thousands of characters to knowing the strict association between the sound of a word and the meaning of that word.

Abjads

An abjad goes one step further, with the clever insight that the fundamental unit of speech is actually the consonant. A consonant is a speech sound that blocks air leaving the vocal tract, and when combined with vowels (non-blocking sounds), forms a syllable. Abjads need only about 20-30 symbols, and encode the most fundamental building blocks of human speech.

Take a moment and just think about how not-obvious this insight is. This insight is so non-obvious, in fact, that the alphabet/abjad, like the wheel or any other civilization-defining technology, was probably invented only once, ever. This means that every alphabet in existence today bears a familial relationship to the very first alphabet ever invented, the Proto-Sinaitic alphabet. With reasonably high confidence, it is proposed that somewhere in the Levant or Lower Egypt, Egyptian Hieroglyphs were adapted into letters in Proto-Sinaitic that each encode one consonant. Strangely enough, the sounds of the hieroglyphs don’t correspond at all to the sounds of their Proto-Sinaitic descendants.

According to William F. Albright,1 credit for the invention of the Proto-Sinaitic script should probably go to either the ancient Canaanites or Hyksos (a mysterious Western Semitic People that conquered Lower Egypt circa 1600 BC). T.E.D. on history.stackexchange explains that Western Semitic speakers are uniquely suited to invent an abjadic script, because their syllable structure is extremely rigid. Every syllable in these languages has a single unique consonant, making the abjad a natural way of expressing a Semitic language. By contrast, an abjad is not a natural way to express English, which has combinations of consonants like “sk” and “pl” that don’t lend themselves to single characters.

Alphabets, Abugidas, and Featural Alphabets

The Ancient Greeks had a further insight — they explicitly encoded vowel sounds as separate symbols in their script, making the first true alphabet out of the Phoenician abjad.

Abugidas are a sort of hybrid system between syllabaries and alphabets, where multiple alphabetic symbols are combined into syllable-like or word-like glyphs. They look really cool, and are easier to learn than syllabaries.

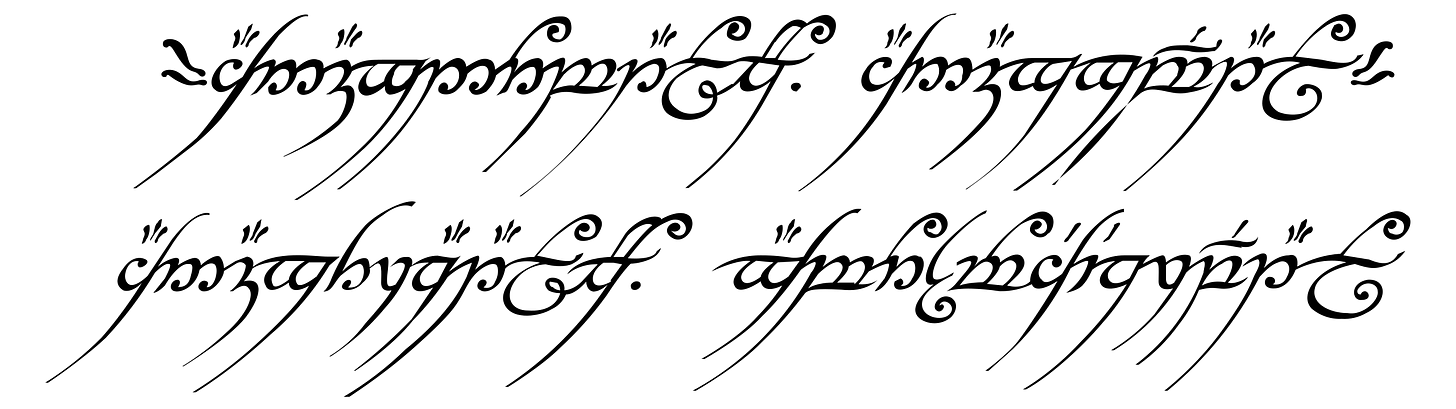

And Hangul, the Korean alphabet, is the first featural alphabet invented, meaning that the glyphs aren’t random, but encode aspects of how the sound is created. This article from the somethingmarvelousblog discusses featural scripts in the context of Tengwar, J.R.R Tolkien’s fictional (and beautiful Elvish) script.

And because I love Egyptian…

Finally, Egyptian hieroglyphs is a weird combination of all of these methods, has about 700 unique glyphs, includes an abjad, additional glyphs that represent two or three consonants (a multi-syllabary?) and a bunch of ideograms. To be fair to them, they may have invented the concept of writing (independently from the Sumerians), so maybe they get a pass for utter lack of thematic consistency. My very first article was about exactly this!

Symbol and Stroke Counts for Alphabets/Abjads/Abugidas/Syllabaries

Just for fun, I plotted some data collected by Changizi and Shimojo in their paper Character complexity and redundancy in writing systems over human history.

As you can see, abjads have character counts in the ~20s, alphabets in the ~30s, abugidas in the ~40s, and syllabaries from 50-90. Changizi and Shimojo also count “number of strokes per character” in each of these systems, and find that it’s roughly constant at 3. This is mildly surprising to me, as I would expect that systems with more characters should have more strokes/character, but I suppose there’s a lot more ways to draw a squiggly line than possible human sounds.

The Alphabetic Phylogeny

Back to the evolutionary relationships of writing systems! The following excellent graphic summarizes the evolution of a bunch of historic and modern alphabets from their common ancestor, Egyptian.

This graphic brings us back to the relationship between Arabic and Hebrew. This chart shows that these scripts are two branches off of the Semitic abjad tree, and their nearest common ancestor is a script called Aramaic, which is both a script and a language. Incidentally, Aramaic is the language that Jesus of Nazareth spoke.

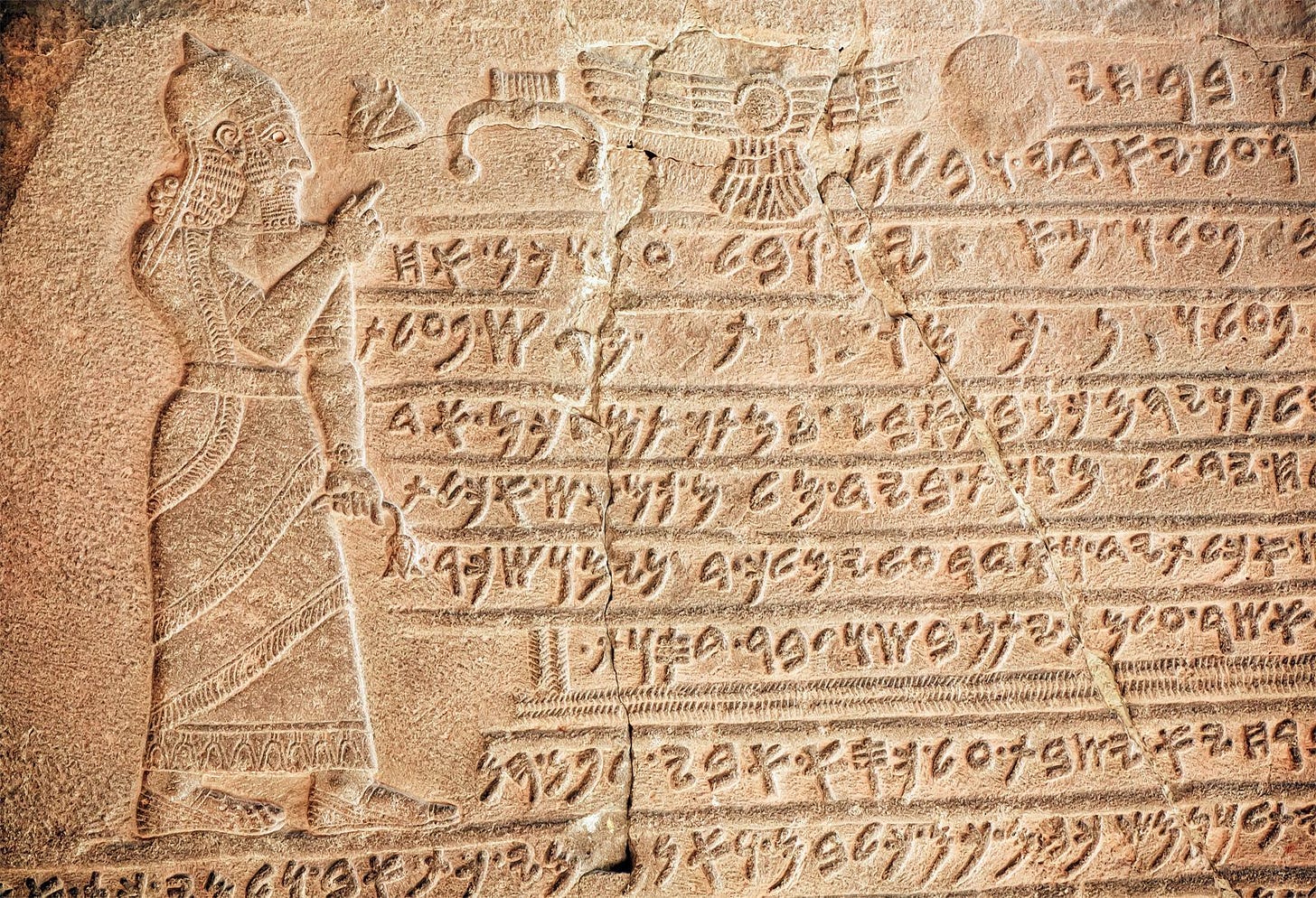

Throughout history, in eras where societies with different relationships have dense economic connections, there usually appears a lingua franca, a trade language that is generally understood and used as a medium for exchange between communities. In the Ancient Near East, this first common tongue was Akkadian. Akkadian, which has a cumbersome cuneiform writing system, was gradually replaced by Aramaic, which has a simple alphabetic writing system that very likely drove its popularity. Aramaic was standardized during the time of the Late Neo-Assyrian empire (whose magnificent kings love replying to spam texts). This standardized Aramaic is known as Imperial Aramaic, and flourished during the Achaemenid Persian Empire.

The Achaemenid Persian empire was a dominant force in the Ancient Near East until the rise of Alexander the Great, and, not coincidentally, controlled or influenced both the Levant (where Hebrew writing developed) and Arabia. Naturally, the native peoples adapted the imperial script to their own languages.

Let’s compare the three scripts, along with the closely related Syriac script.

There’s a pretty clear path from Imperial Aramaic to Hebrew, and a parallel, slightly less clear line from Imperial Aramaic to Syriac to Arabic.

So there we go! Arabic and Hebrew are cousins on both the language and the script family tree. Their evolutionary relationship becomes much more clear when we look at a common ancestor, instead of a direct comparison.

Towards the Latin Alphabet

That’s essentially the end of the post! I’ve got a couple more cool things though, so bear with me.

First, on slightly different branch of the Alphabet Family Tree, sits the Greek Alphabet, the first true alphabet, and the ancestor of the Latin alphabet in which this post is written. This next graphic summarizes its evolution from Proto-Sinaitic, and it’s very pretty:

Remember to take these charts with a grain of salt! There’s no really good way to prove genetic inheritance of scripts.

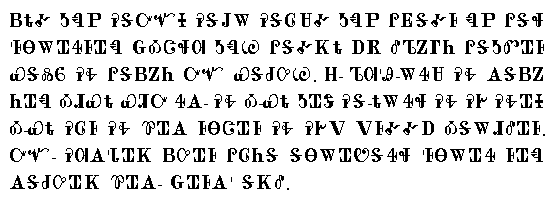

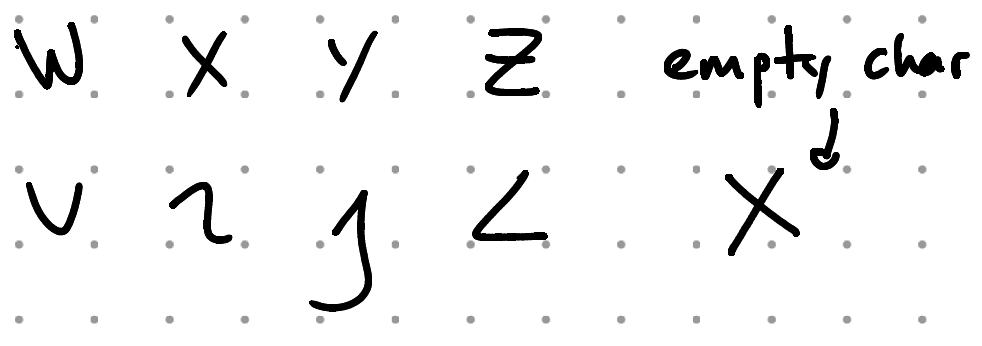

My Own Alphabet, Just for Fun

I’ve always liked looking at pretty, unique scripts, which is why I decided to write this post in the first place. I also especially enjoy inventing my own. One day, when I was bored in eighth grade, I made my own secret alphabet in which I would write notes that only I could read. I designed it for easy readability — by removing strokes from the Latin alphabet, I could still easily recognize the letters I was familiar with, and read it almost as fast as English. I also adopted some stylistic choices from Tolkien’s Tengwar script, which I still love today.

Here is a modern variation on this ancient script, first attested in California, 2008:

To this day, none but a select group of scholars can translate this mysterious writing.

Albright, William F. (1966). The Proto-Sinaitic Inscriptions and their Decipherment.

Great work!

I am doing a study in this line. I am a Neuroscientist.

Thank you for sharing your knowledge and wisdom and wishing you the best!

Kind regards

A fun article.

Re: Strokes per character. I would expect the number of strokes in a character to correlate with the frequency of use of the character, i.e., more frequently used characters having fewer strokes.