Minutiae from the Ancient World

Ancient customer reviews, raunchy graffiti, grisly records of torture, and actually valid pregnancy tests. The Ancient World has it all!

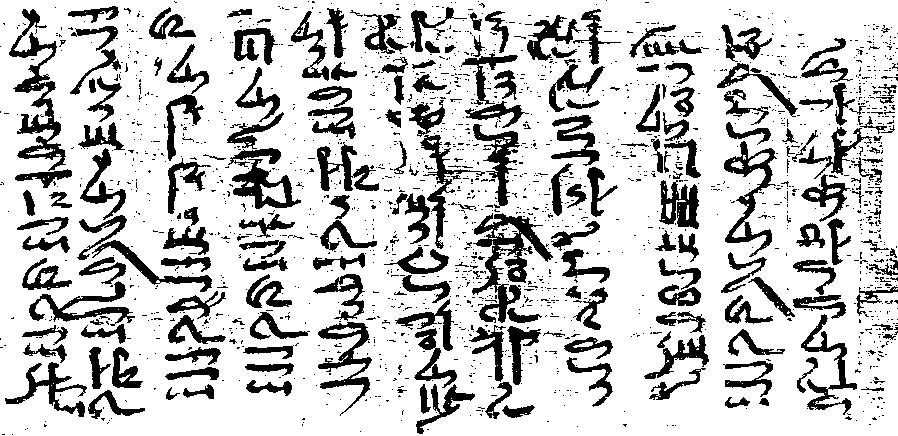

Writing is a form of telepathy. Some time in the Egyptian Middle Kingdom (~2000 BCE), a living, breathing person somewhere in the Nile Valley carefully painted hieratic symbols onto a sheet of papyrus. Four thousand years later and two continents away, I read his words — The Tale of the Shipwrecked Sailor — from the comfort of my bed.

Writing is so commonplace now that it’s almost banal, but to the ancients, it was like magic. Writing frees the mind from memorization. It can carry my exact phrasing thousands of miles from where I said it without error. It preserves a man’s thoughts a thousand years after his death.1

Ancient texts are fascinating, because contained within them are universal human sentiments so strikingly familiar that you feel a deep, human connection with a person dead for a hundred generations. Other times, you can get a taste of just how different the ancients’ fundamental assumptions about the world were. You can also marvel at the sheer brutality they displayed, completely at odds with modern sentiments. You can even do all three at once, with the right inscription.

Since I want more people to share my hobby, I’ve collected a few of my favorites here for you, some familiar, some foreign, some savage, and all fascinating.

The First Customer Complaint in History

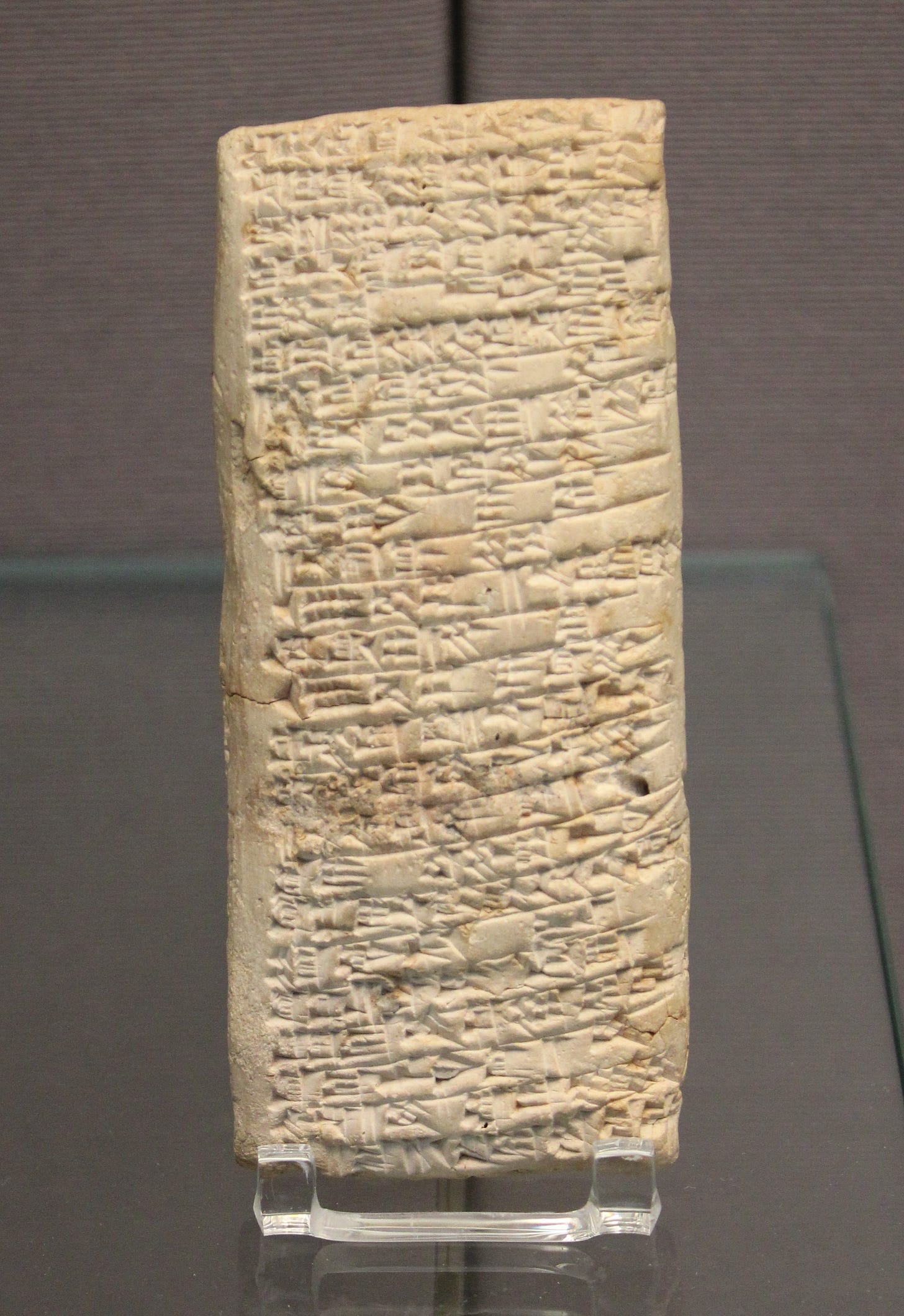

This is one of my very favorite ancient texts, called the “Complaint Tablet to Ea-Nasir.”2

Tell Ea-nasir: Nanni sends the following message:

When you came, you said to me as follows: “I will give Gimil-Sin (when he comes) fine quality copper ingots.” You left then but you did not do what you promised me. You put ingots which were not good before my messenger (Sit-Sin) and said: “If you want to take them, take them; if you do not want to take them, go away!”

What do you take me for, that you treat somebody like me with such contempt? I have sent as messengers gentlemen like ourselves to collect the bag with my money (deposited with you) but you have treated me with contempt by sending them back to me empty-handed several times, and that through enemy territory. Is there anyone among the merchants who trade with Telmun who has treated me in this way? You alone treat my messenger with contempt! On account of that one (trifling) mina of silver which I owe you, you feel free to speak in such a way, while I have given to the palace on your behalf 1,080 pounds of copper, and Shumi-abum has likewise given 1,080 pounds of copper, apart from what we both have had written on a sealed tablet to be kept in the temple of Shamash.

How have you treated me for that copper? You have withheld my money bag from me in enemy territory; it is now up to you to restore (my money) to me in full.

Take cognizance that (from now on) I will not accept here any copper from you that is not of fine quality. I shall (from now on) select and take the ingots individually in my own yard, and I shall exercise against you my right of rejection because you have treated me with contempt.

Ea-Nasir is apparently just the worst businessman. Not only did he deliver the wrong grade of copper to Nanni, but when Nanni complained, Ea-Nasir sent his messenger back empty-handed through enemy territory! All this after Nanni gave 1,080 pounds of copper to the temple on Ea-Nasir’s behalf!

According to Forbes, this tablet was found in Ea-Nasir’s house in Babylon, next to a bunch of similar complaint letters. It’s a bit ironic that where countless mighty kings have had their names erased from history by the passage of time, Ea-Nasir was so bad at delivering copper that his name has been preserved for four millennia. There’s a profound truth there, but I’m not sure what it is.

Ancient Graffiti

This is a picture of some graffiti I found on the wall of UC Berkeley’s statistics building:

Whenever I find graffiti like this, especially in public bathrooms, the first thing I wonder is always “why were they carrying around a permanent marker?”

But public graffiti, especially the explicit stuff, has a loooong history. There are at least two runic inscriptions in the Hagia Sophia, a Byzantine Church, written by visiting Vikings, which probably say “Halfdan carved these runes” and “Ari carved these runes.”

Graffiti can be extremely important for historical reasons. For example, Queen Hatshepsut, the second female pharaoh of Egypt, may have taken her steward Senenmut as her lover.

How do we know this?

Well, archaeologists uncovered this drawing near her mortuary temple at Deir al-Bahari, probably carved by the workmen who built it, showing the Queen and Senenmut in a… compromising position:

The impulse to draw penises and rude drawings on things is universal among young boys — having been one, I can personally attest to this. As such, my very favorite example(s) of historical graffiti come from Pompeii, that Roman city preserved by the disastrous Mount Vesuvius eruption of 79 CE. Here’s a selection from Kashgar.com. As a side note, The Ancient Graffiti Project is awesome and well worth reading.

In no particular order, here are the explicit ones:

Bar/Brothel of Innulus and Papilio: Weep, you girls. My penis has given you up. Now it penetrates men's behinds. Goodbye, wondrous femininity!

Gladiator barracks: Floronius, privileged soldier of the 7th legion, was here. The women did not know of his presence. Only six women came to know, too few for such a stallion.

Street wall: Theophilus, don't perform oral sex on girls against the city wall like a dog

Vico d' Eumachia, brothel: Gaius Valerius Venustus, soldier of the 1st praetorian cohort, in the century of Rufus, screwer of women

In the basilica: Chie, I hope your haemorrhoids rub together so much that they hurt worse than when they ever have before!

These are basically Yelp reviews:

House of Cuspius Pansa: The finances officer of the emperor Nero says this food is poison

Wood-Working Shop of Potitus, next to a bar: Would that you pay for all your tricks, innkeeper. You sell us water and keep the good wine for yourself

Herculaneum bar: Two friends were here. While they were, they had bad service in every way from a guy named Epaphroditus. They threw him out and spent 105 and half sestertii most agreeably on whores

These are just adorable:

Bar: We two dear men, friends forever, were here. If you want to know our names, they are Gaius and Aulus.

Atrium of the House of Pinarius: If anyone does not believe in Venus, they should gaze at my girlfriend

And these are #deep:

In the basilica: The one who buggers a fire burns his penis

In the basilica: O walls, you have held up so much tedious graffiti that I am amazed you have not already collapsed in ruin

Inn of the Muledrivers; left of the door: We have pissed in our beds. Host, I admit that we shouldn't have done this. If you ask: Why? There was no potty

The Definitely 100% True Story of How Darius the Great Became King of Persia

Switching gears from the raunchy and mundane world of ancient graffiti (drawings by commoners), we come to “royal inscriptions” (still drawings by commoners, but ordered by kings).

Have you ever heard a story that’s just so wildly implausible that you circle all the way around from total disbelief to shocked awe? A story that’s just so clearly false that you have to admire the chutzpah of the one who told it?

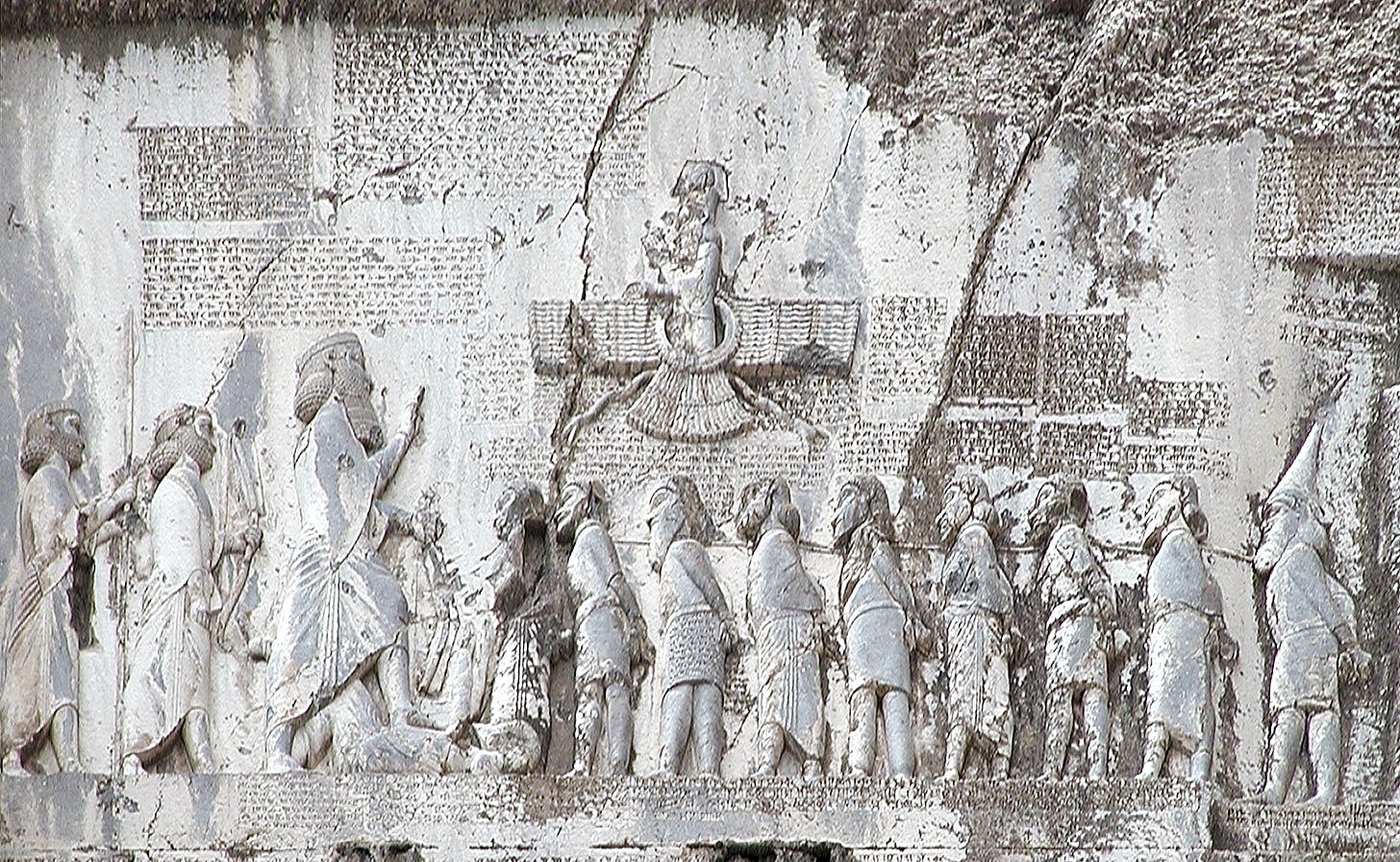

Darius the Great, third king of the Persian Empire, took power in a coup by killing the previous king. However, he has his own positively juicy version of events where he is entirely blameless, and to make sure that everyone knew it, he carved his story into the sacred mountain at Behistun. At the time, the Persian language didn’t have a writing system, so naturally he invented a new one for this express purpose.

Here’s an abridged and lightly edited version of the Behistun Monument translation, courtesy of Livius.org:

King Darius says:

A son of Cyrus, named Cambyses, was king here before me. Cambyses had a brother, Bardiya by name, of the same mother and the same father as Cambyses. Cambyses slew Bardiya, but it was not known to the people that Bardiya was slain.

When Cambyses had departed into Egypt, the people became hostile, and the Lie multiplied in the land. (the Lie, with a capital L, is a Persian/Zoroastrian concept of evil and chaos, opposed by the concept of cosmic Truth).

Afterwards, there was a certain man, a Magi named Gaumâta, who raised a rebellion. He lied to the people, saying: "I am Bardiya, the son of Cyrus, the brother of Cambyses." The people went over to him, and Gaumâta seized the kingdom.

Afterwards, Cambyses died of natural causes.

The people feared Gaumâta exceedingly, for he slew many who had known the real Bardiya. There was none who dared to act against Gaumâta, the Magi, until I came.

Then I prayed to Ahuramazda; Ahuramazda brought me help. On the tenth day of the month Bâgayâdiš, with a few men, I slew Gaumâta, and the chief men who were his followers. At the stronghold called Sikayauvatiš, in the district called Nisaia in Media, I slew him; I dispossessed him of the kingdom. By the grace of Ahuramazda I became king; Ahuramazda granted me the kingdom.

The temples which Gaumâta the Magi had destroyed, I restored to the people, and the pasture lands, and the herds and the dwelling places, and the houses which Gaumâta the Magi had taken away. I restored that which had been taken away, as is was in the days of old. This did I by the grace of Ahuramazda.

This is a ridiculous story. It reads like the plot of a Mission: Impossible movie. Cambyses the prince slew the only other prince of the royal house, and no one noticed? Then, years later, someone shows up claiming that he’s the dead crown prince, and everyone buys this, including the remaining members of his own family? Cyrus the Great had many daughters, not just two sons, who were alive and would definitely know their brother, by the way.

Let me propose a slightly less ridiculous version of events: Cambyses the king died, Cyrus’ other son Bardiya became king, Darius staged a coup, killed Bardiya, and completely made up the story about the Magi Gaumâta impersonating Bardiya. Dan Carlin’s Kings of Kings podcast tells the story best, I think, but I also love the more historically inclined History of Persia podcast, which tells the same story with a more scholarly bent.

I just love this story. It has everything — a murder mystery, a Magus impersonating a king, a Force 10 from Navarone style hit job on a reigning monarch (thanks to Dan Carlin for the metaphor), and it’s carved into a sacred mountain to make damn sure that everyone knew that this was the version of events we’re going with, and you’d better get in line. Finally, because this inscription was tri-lingual, it was instrumental in deciphering not just Old Persian, but two other ancient languages as well, Akkadian and Elamite. Just awesome.

Inscriptions of Assyrian Conquest

Continuing with the theme of awe-inspiring ancient royal inscriptions, we have to acknowledge the Assyrian Kings. They turned royal propaganda into a psychological weapon against their enemies, the idea being that they were so brutal to their enemies that no one in their right minds would ever rebel against them. One of the reasons ancient history is so interesting to read is that you just don’t get modern proclamations that sound like this one, where Ashurnasirpal records what he did to the nobles of a rebellious city:3

I flayed as many nobles as had rebelled against me [and] draped their skins over the pile [of corpses]; some I spread out within the pile, some I erected on stakes upon the pile … I flayed many right through my land [and] draped their skins over the walls.

Whoa. Here’s another sample of Ashurnasirpal’s, uh, style:

In strife and conflict I besieged [and] conquered the city. I felled 3,000 of their fighting men with the sword … I captured many troops alive: I cut off of some their arms [and] hands; I cut off of others their noses, ears, [and] extremities. I gouged out the eyes of many troops. I made one pile of the living [and] one of heads. I hung their heads on trees around the city.

It’s not just Ashurnasirpal, though. Every single Assyrian king sounds exactly like this. Here’s a sample of Sennacherib’s inscriptions nearly two hundred years later:

I cut their throats like lambs. I cut off their precious lives (as one cuts) a string. Like the many waters of a storm, I made (the contents of) their gullets and entrails run down upon the wide earth. My prancing steeds harnessed for my riding, plunged into the streams of their blood as (into) a river. The wheels of my war chariot, which brings low the wicked and the evil, were bespattered with blood and filth. With the bodies of their warriors I filled the plain, like grass. (Their) testicles I cut off, and tore out their privates like the seeds of cucumbers.

My god, the imagery there. And I mean this literally, because not only did the Assyrians write this stuff, they carved it into their palaces too:

Yes, that is a tower of heads. Hats off (literally) to the Assyrians, they knew what they were after and made no bones about it.

Recommended Reading: Grisly Assyrian Record of Torture and Death.

Egyptian Pregnancy Tests

I want to end on a lighter note, and to that end I want to share with you the very first legitimate pregnancy test.4 Modern pregnancy tests work by checking your urine for Human Chorionic Gonadotropin (HCG), which is a hormone released when a fertilized egg attaches to the uterus wall. The Ancient Egyptian version was actually pretty similar. Here is what the Berlin Medical Papyrus says:

Another test for a woman who will bear [children] or not bear [children]. Wheat and spelt: let the woman water them daily with her urine, like dates and sh’at seeds in two bags. If they both grow, she will bear [a child]. If the wheat grows, it will be a boy. If the spelt grows, it will be a girl. If neither grows, she will not bear [a child].

In plain English, you put wheat grains in one bag, and spelt grains in another bag, and have the woman pee on them. If the wheat grows, she’s pregnant with a boy, if the spelt grows, she’s pregnant with a girl. If neither grow, she isn’t pregnant.

Incredibly, modern researchers tried this out, and they found that in 28/40 cases, the urine of a pregnant woman caused one or both types of grain to grow! They also did a control experiment with 8 samples of non-pregnant urine, and observed no growth in any of these cases. The Egyptian pregnancy test is ~70% effective! The authors conclude that the following statement is justifiable: “when barley and wheat are watered with urine, if any or both kinds of grains grow, the urine comes from a pregnant woman.”

Unfortunately, the test was completely ineffective at determining the sex of the child. But then again, modern (urine based) pregnancy tests don’t do that either.

I hope you’ve enjoyed reading this article as much as I’ve enjoyed writing it. The Ancient World is an incredible place, filled with people who are simultaneously completely foreign and strikingly familiar. One day, I will be one of those unfathomable ancient peoples. And so, to any crypto-archaeologists or techno-historians of the distant future who may be reading this, my name is Dylan S. Black, son of Alistair and Deborah, writing on the Fifth of January, 2022 CE, and I salute you.

Credit to the Oldest Stories podcast for some of the phrasing

Letters From Mesopotamia: Official, Business, and Private Letters on Clay Tablets from Two Millennia, by A. Leo Oppenheim, page 82. https://oi.uchicago.edu//research/publications/misc/letters-mesopotamia-official-business-and-private-letters-clay-tablets

Grisly Assyrian Record of Torture and Death, by Erika Belibtreu. Editor, H. S. (2002;2002). BAR 17:01 (Jan/Feb 1991). Biblical Archaeology Society. https://faculty.uml.edu//ethan_spanier/teaching/documents/cp6.0assyriantorture.pdf

ON AN ANCIENT EGYPTIAN METHOD OF DIAGNOSING PREGNANCY AND DETERMINING FOETAL SEX, by P. Ghalioungui, SH. Khalil and A. R. Ammar. Medical History, Volume 7, Issue 3. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/medical-history/article/on-an-ancient-egyptian-method-of-diagnosing-pregnancy-and-determining-foetal-sex/14D30302A038355CB787358800D17D44

Update! I came across this ancient Egyptian tablet listing excuses for why people didn’t show up at work.

Here’s a list of all the excuses compiled by user jamesfisher on Hackernews:

67 ILL

49 WITH HIS BOSS

17 BREWING BEER

13 WITH AAPEHTI

8 WITH THE SCRIBE

6 MAKING REMEDIES FOR THE SCRIBE’S WIFE

5 WRAPPING (THE CORPSE OF) HIS MOTHER

5 OFFERING TO THE GOD

5 HIS WIFE WAS BLEEDING

5 FETCHING STONE FOR THE SCRIBE

4 WITH KHONS MAKING REMEDIES

4 SUFFERING WITH HIS EYE

4 OFF ABSENT

4 HIS DAUGHTER WAS BLEEDING

3 WITH HOREMWIA

3 WITH HIS BOSS DITTO

3 LIBATING TO HIS FATHER

2 WRAPPING (THE CORPSE OF) HIS SON

2 HIS MOTHER WAS ILL

2 HIS FEAST

2 FETCHING STONE FOR QENHERKHEPSHEF

2 BURYING THE GOD

1 WITH HIS GOD

1 THE SCORPION BIT HIM

1 STRENGTHENING THE DOOR

1 OFFFERING TO THE GOD

1 OFFERING TO HIS GOD

1 OFF ABSENT WITH THE SCRIBE

1 MOURNING HIS SON

1 LIBATING FOR HIS SON

1 LIBATING FOR HIM

1 LIBATING

1 EMBALMING HORMOSE

1 EMBALMING HIS BROTHER

1 DRINKING WITH KHONSU

1 BUILDING HIS HOUSE