An Offering for the Dead

A Short Tutorial on Reading Ancient Egyptian

To speak the name of the dead is to make them to live again.

Minimum Effort, Maximum Reward

A long, long time ago, I watched a hilarious Collegehumor video about learning guitar just well enough to impress girls. In their words, there are literally thousands of chords you could learn, but only four of them are needed to play Wonderwall.

That’s basically what I want to do here. In this article, and in a total reversal of this blog’s theme, I’m going to teach you just enough Ancient Egyptian to impress your friends, by learning five key phrases.

Ancient Egypt, as a culture, placed unusual emphasis on funerary rites. As such, many of the artifacts that have come down to us are death, tomb, and burial-related. In Egypt, burials were very religious and heavily ritualized, and one aspect of Egyptian burials is a standardized litany for the dead, known as the offering formula, which shows up on fully half of the artifacts you’re likely to see in a museum.

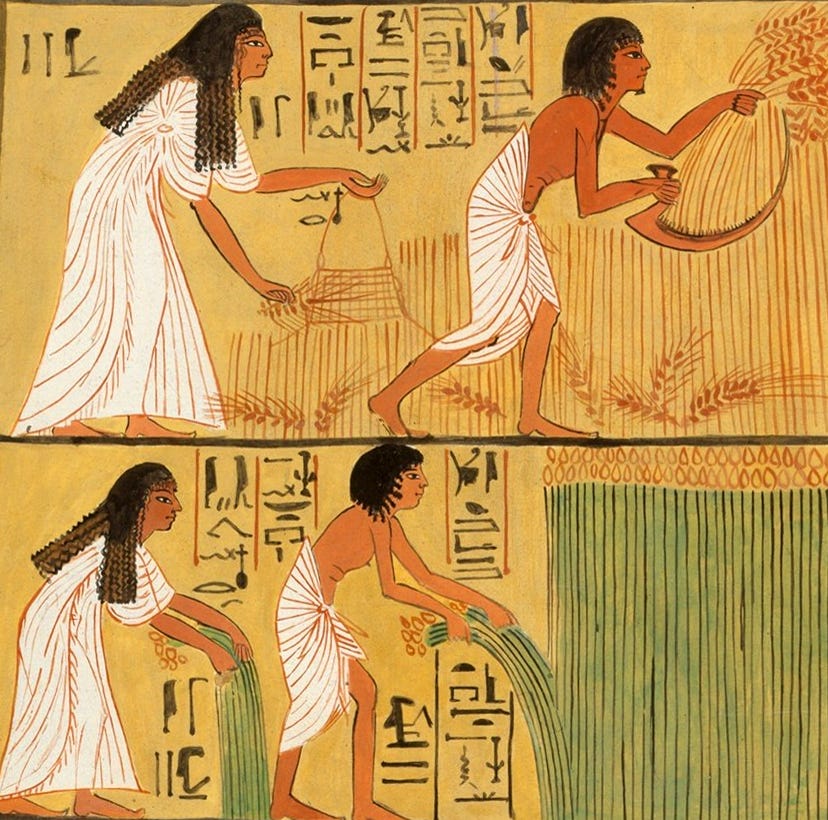

This is the stela from the Wikipedia article on the offering formula, which I will refer to for examples:

And this is an idealized offering formula, transcribed for easier reading:

I’m going to break this formula down for you, because it’s quite easy to recognize, and incredibly common. Parts of the formula change from stela to stela, but parts of the formula are completely rigid, appearing exactly the same way with exactly the same symbols on every single inscription for 3,000 years.

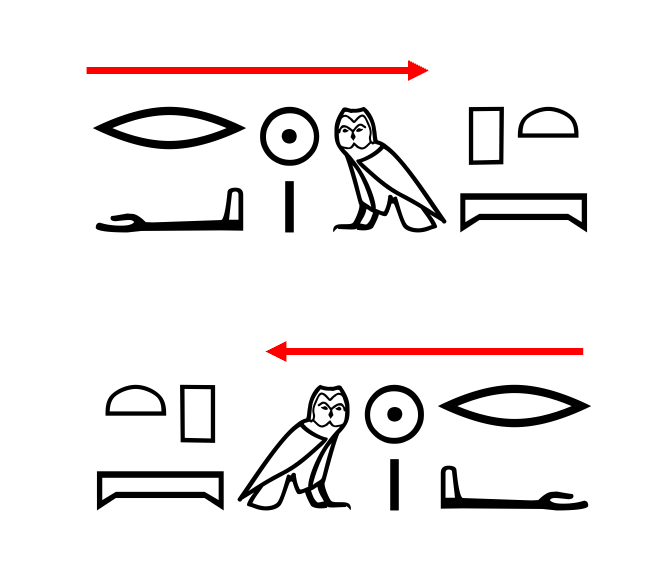

Reading Direction

First things first, we have to know the reading direction, because hieroglyphs can be read left to right, right to left, or up to down. To find the correct direction, first find a bird. Read into the faces of the birds/humans/snakes/etc.

The birds, humans, crocodiles, etc., always face the front of the sentence.

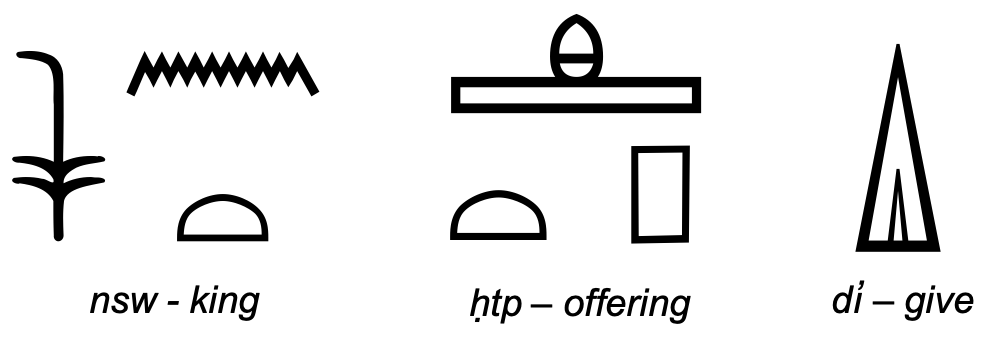

1. An Offering Given by the King

The first part of the offering formula is basically an Ancient Egyptian acronym. I’ve written before about the mechanics of the Ancient Egyptian Language (and dirty emoji chain letters) — Egyptian is actually neither alphabetic nor ideographic, but a mixture of both. However, for the hyper-abbreviated, hyper-standardized offering formula, we don’t have to worry about any of the specific details.

The offering formula begins with a statement that this offering is given by (or authorized to be given on behalf of) the king. It is transliterated ḥtp-di̓-nsw and pronounced something like “ho-tep dee nah-soo:”

These three signs are taken from three Egyptian words:

and together, they mean “an offering which the king gives,” or “an offering given by the king.”

Here it is on our sample stela:

2. To Osiris, Lord of Abydos

The hieroglyphs immediately following ḥtp-di̓-nsw always invoke a god, usually Osiris or Anubis or some other god associated with death, followed by his epithets.

Here’s the names of some common gods that appear in the offering formula:

Above each hieroglyph, I’ve put the uni-literal (one letter) or bi-literal (two letters) to which it corresponds. The other (more complex) signs are labeled Det. for “Determinative,” which is a type of idea-sign that classifies or determines the signs preceding it. My previous article goes into this in a bit more depth.

The gods usually come with epithets. In case you don’t know what an epithet is, here are some of my favorite examples, from the Frankish royal family:

I think we should name all our leaders and politicians like this.

Anyway, in this case, the word “Osiris” is followed by three of his epithets: “Osiris, Foremost of the Westerners, the Great God, Lord of Abydos.” The Egyptians believed that the dead rested in the west, and so here we see “Westerner” being used as a euphemism for the dead, much like “the departed” is used in English.

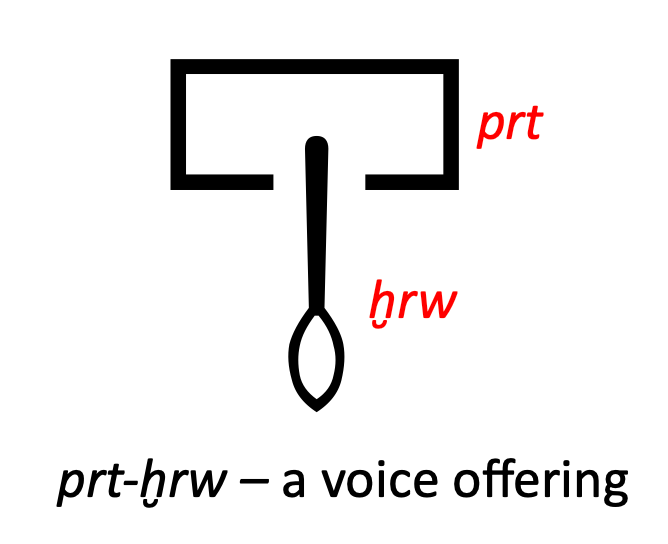

3. A Voice Offering of Bread and Beer

So the king gives an offering to Osiris. What does he give? The Egyptians believed that the dead needed sustenance in the afterlife — bread, beer, etc. In place of real offerings of bread and beer, words or pictures of bread could substitute. This is the next part of the offering formula: the voice offering, or prt-ḫrw (pronounced “per-et khair-oo”).

Reciting the voice offering provides the dead with offerings in the afterlife.

In the stela from Wikipedia (which I should probably refer to by its actual name, the “Stela of Pepi”), we see the hieroglyph for “voice offering” followed by all the things that the dead person would receive if you said the offering formula for them.

This is everything that an Egyptian would need in the afterlife!

4. For the Ka of…

After the description of the voice offering comes a ritualized phrase introducing the person for whom this offering is made.

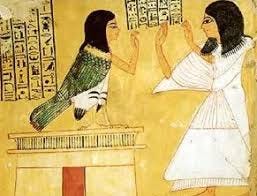

Oversimplifying a bit, the modern concept of a “soul” maps loosely onto two different Egyptian beliefs, the ka, usually translated as “life force,” and the ba, usually translated as “soul.” The ka is your life force, which must be sustained after death, hence the offerings of bread, beer, etc. The ba is something more like personality, and is usually represented as a human-faced bird.

The ka of the deceased requires food, and must be explicitly named by the offering formula. To speak the name of the dead is to cause them to live, after all. Thus, the words directly following “for the ka of” is usually the name of the deceased, plus or minus some honorary titles.

Sometimes, but not always, the following name will contain a seated man or seated woman determinative, which can help pinpoint it.

A Side Note on the Ba

The ba is not a concept that maps easily onto Western conceptions of soul. One of my favorite pieces of Egyptian literature is the Dispute Between a Man and his Ba (and the Wikipedia link for easier reading), where a man wants to kill himself, and his ba tries to talk him out of it. It’s just so weird, and I love it. So did Julian Jaynes, a famous psychologist whose theories inspired Westworld, who claims that the Dispute story is very strong evidence that humans were not conscious before Homer’s Iliad was written. No, really, I’m not making that up, seriously go read The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind, it’s WILD.

5. The Justified Dead

Finally, the name of the deceased person is nearly always followed by the epithet mꜣꜥ-ḫrw, pronounced something like “mah-ah khair-oo.” This means “justified” in the sense of being morally righteous, but translates literally as “true of voice.”

Here are three common ways you’ll see this written:

Basically, look for the trapezoid and the spoon (and remember that they can be sideways). The trapezoid looks like a line most of the time, so really, look for the line and the spoon.

This is a great way to identify names in stelae! If you find the line and the spoon, the hieroglyphs directly preceding it are the person’s name (and/or titles). I’ve never seen an exception to this rule (though I’m sure some exist).

Egyptian Word Search!

Here’s a stela from the Brooklyn Museum that my friend asked me to translate for him a few days ago. Try out what you’ve learned by finding the five phrases! Hint: the reading direction changes from column to column. An answer key can be found further down.

Happy reading!