Pimps, Diks, and Bumfits

This is a facebook message I got from my friend Sunil Pai the other day:

Upon seeing this message, most English speakers will wonder what the hell Sunil and I are talking about.

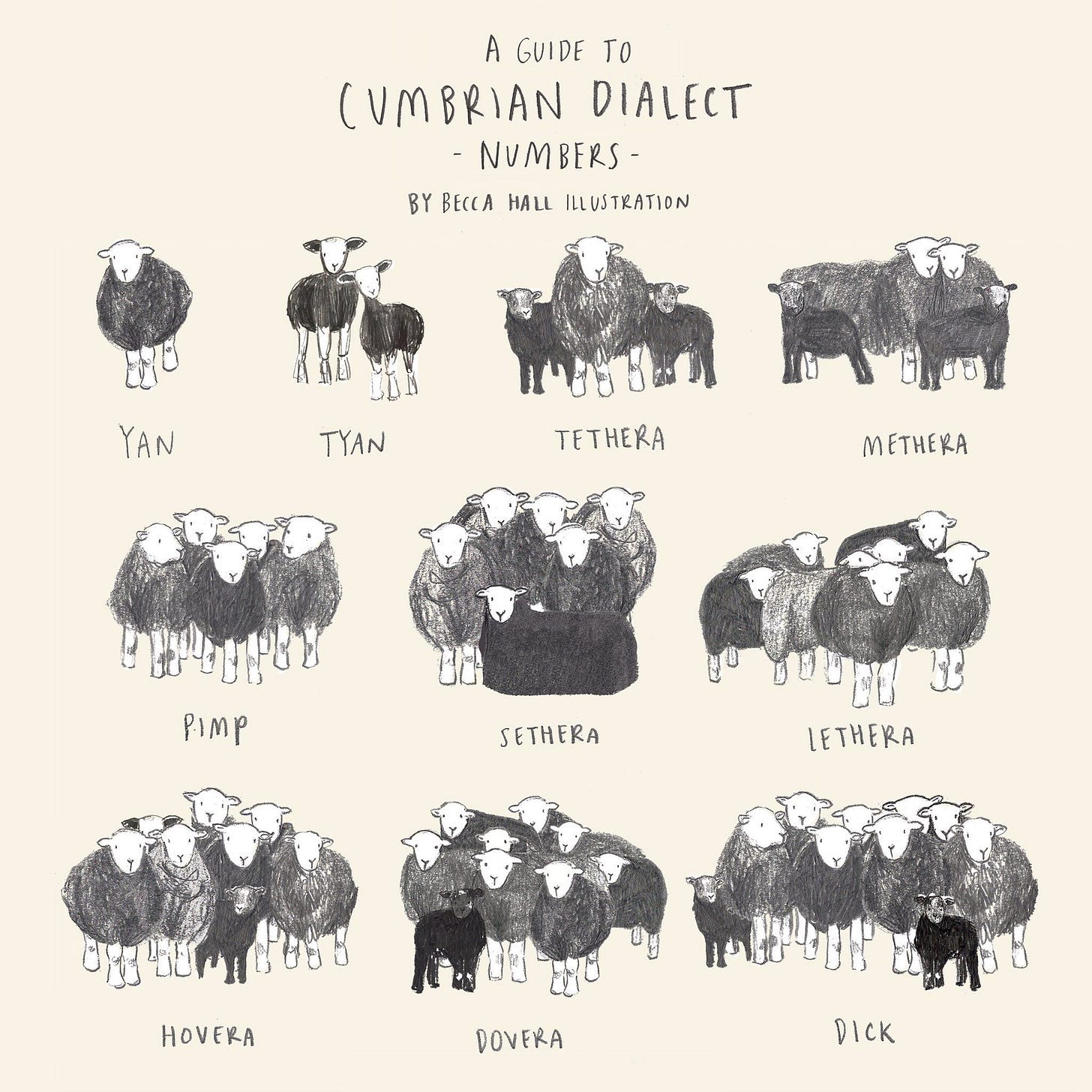

It has to do with a book he’s reading, called Alex's Adventures in Numberland: Dispatches from the Wonderful World of Mathematics. Chapter 1 covers counting systems used in various different societies — the Arara in the Amazon count in pairs, the Revolutionary French tried to make clocks count by tens, and the Babylonians counted in base 60. But the most interesting counting system, to me, was the one used by shepherds in Lincolnshire, England, to count sheep.

Yan

Tan

Tethera

Pethera

Pimp

Sethera

Lethera

Hovera

Covera

Dik

Yan-a-dik

Tan-a-dik

Tethera-dik

Pethera-dik

Bumfit

Yan-a-bumfit

Tan-a-bumfit

Tethera-bumfit

Pethera-bumfit

Figgit

So when Sunil told me that covera pimp dik bumfit and bumfit pimp dik was 69, all he really said was that 9 + 5 + 10 + 15 + 15 + 5 + 10 = 69, which is true.

I find this counting system fascinating, and not just because counting pimp, dik, bumfit, figgit is hilarious and fun.

First of all, you’ll notice that this system is a hybrid base-five, base-twenty counting system. You have unique words up to ten, then compound words (Tan-a-dik = Tan + dik = twelve) up to fifteen (bumfit), then some more compounds with bumfit up to figgit (twenty).

Secondly, this counting system felt weirdly familiar to me. Yan and one, tan and two, tethera and three, pethera and four. What about dik? Well, this is clearly similar to dec, the Latin root for ten (French is dix, Spanish is diez, Italian is dieci). Even figgit looked familiar — the Latin vīgintī, meaning twenty, sounds a lot like figgit. My first thought was that this system is some kind of corrupted Latin, mixed with whatever Celtic language existed in Lincolnshire before the Roman conquest.

I wasn’t right about this, but I was close.

Consonant Shifts and Proto-Indo-European

Why does pethera, which begins with a “p,” sound familiar to four, anyway?

Consonant shift! Linguists have discovered regular patterns of consonant shift that occur as languages evolve. The most famous of these sound shifts are the shifts that transform Proto-Indo-European into its daughter languages (Latin, English, Sanskrit, Persian, etc.).

Grimm’s Law states that the Proto-Indo-European consonants underwent predictable, regular evolution as they evolved into Proto-Germanic and Germanic daughter languages.

For example, the Proto-Indo-European word for “brother,” bʰréh₂tēr (something like “breh-ter”) evolved into the Proto-Germanic brōþēr (“bro-ther”), and eventually into the Old English broþor (“bro-thor”).

By the way, that funny letter þ is called thorn, which is an Old English letter pronounced “th.” If you had to read Beowulf in high school English class, you might remember seeing þ all over the place.

“Father” is another good example of regular consonant shifts. Proto-Indo-European *ph₂tḗr (“peh-ter”) evolved into Proto-Germanic *fadēr, and eventually Old English fæder.

So “p” and “f” are linguistically very similar, especially in a Germanic language like English. Pethera and four could easily be derived from a common Indo-European ancestor.

The idea is similar with vīgintī (Latin) and figgit (Lincolnshire shepherd’s dialect). The “f” and the “v” are very similar sounds, followed by “g” and “t” sounds. Try pronouncing “vigint” ten times fast and see if it morphs a little into “figgit.”

It was at this point, while googling consonantal shifts, that I found this video from Numberphile, with one of the least searchable titles I’ve ever seen. From Numberphile, I present the gloriously titled 15 bumfit:

In the video, Professor Roger Bowley says that the yan-tan-tethera number system is Celtic, and predates the Roman conquest of Britain. So my theory of corrupted Latin is wrong — actually, both Latin and this obscure Celtic dialect have a common ancestor in Proto-Indo-European!

This explanation of the yan-tan-tethera origin fits much better than mine does. Wikipedia has a whole list of different variations on the yan-tan-tethera counting system for various English regions.

Apparently this weird-ass counting system is actually a very old counting system that probably predates the Roman conquest of Britain, and it’s linguistically related to all the other Indo-European languages! Some of the words are even the same!

But wait, what about bumfit?

Consider the bumfit, and make sure it’s hovera covered

Bumfit is a hilarious word. However, I don’t think “bumfit” sounds like “fifteen” at all. Nor does “hovera, covera” sound like “eight, nine” in any way. But if all the numbers in the yan-tan-tethera counting system are derived from Proto-Indo-European, how did eight and nine (*h₃eḱteh₃ and *h₁néun in Proto-Indo-European) become hovera, covera?

The explanation from the same Wikipedia page says that bumfit and the rest are Proto-Celtic numerals that died out in modern English. The Welsh numerals do have something in common with the yan-tan-tethera system:

The Welsh pymtheg is… sorta similar to bumfit, I guess? And the Welsh pump, deg, pymtheg, ugain is at least partially recognizable as pimp, dik, bumfit, figgit.

The Ancient British word for twenty, wikantī, is essentially identical to the Latin vīgintī (remember, in classical Latin, “v” is pronounced “w”), so I guess the Wikipedia page’s claim that multiples of five are highly conserved checks out.

But this hypothesis seems somewhat lacking to me. Where do you get hovera (8) and covera (9) from? The Welsh versions are wyth and naw, and the Ancient British versions are oxtu and nawan. That’s not even close.

Counting Rhymes

Another friend of mine, Jill, mentioned to me that she had just finished reading The Writing of the Gods: The Race to Decode the Rosetta Stone, and it had mentioned that the children’s nursery song “Hickory Dickory Dock, the mouse ran up the clock” was originally a counting rhyme.

Short, common words, learned early in life, tend to be the most constant throughout language evolution (“mama,” “father,” “brother,” etc.). In the same way, counting rhymes, taught to children at a young age, are highly conserved linguistically.

This led me to the fantastic article The Secret History of "Eeny Meeny Miny Mo,” by Adrienne Raphel, on the origin and history of counting rhymes. Seriously, give this article a read, it’s fascinating.

I would venture a guess that pretty much every English-speaking schoolchild knows some version of the the rhyme:

Eeny, meeny, miny, mo

Catch a tiger by the toe

If he hollers, let him go

Eeny meeny miny mo

This rhyme has a darker history than I knew. According to Adrienne Raphel,

In the canonical Eeny Meeny, “tiger” is standard in the second line, but this is a relatively recent revision. If it doesn’t seem to make sense, even in the gibberish Eeny Meeny world, that you’d grab a carnivorous cat’s toe and expect the tiger to do the hollering, remember that in both England and America, children until recently said “Catch a nigger by the toe.”

Didn’t know that one. Yikes. But it seems that this is a fairly recent revision of a much more ubiquitous class of counting rhymes. In Denmark:

Ene, mene, ming, mang,

Kling klang,

Osse bosse bakke disse,

Eje, veje, vaek.

And in Zimbabwe:

Eena, meena, ming, mong,

Ting, tay, tong,

Ooza, vooza, voka, tooza,

Vis, vos, vay.

However, while reading this article, one particular rhyme caught my eye.

In 1830, children in Scotland chanted:

Zinti, tinti,

Tethera, methera,

Bumfa, litera,

Hover, dover,

Dicket, dicket,

As I sat on my sooty kin

I saw the king of Irel pirel

Playing upon Jerusalem pipes.

In that rhyme, found in Scotland, we see “tethera, methera, bumfa, hover, dover, dicket,” all recognizable yan-tan-tethera numbers. Raphel goes on to connect this counting rhyme to the same yan-tan-tethera counting system we’ve been discussing, which she gives as:

Yan, tan, tethera, methera, pimp,

Sethera, lethera, hothera, dovera, dick,

Yan-dick, tan-dick, tether-dick, mether-dick, bumfit,

Yan-a-bumfit, tan-a-bumfit, tethera bumfit, pethera bumfit, gigert.

Now I see what’s going on. The yan-tan-tethera counting system is much more than simply a linguistic evolution of the ancient Proto-Indo-European numbers, it’s a counting rhyme! Likely, it is designed to be a memory aide for a nonliterate population that needs to count things.

Some of the numbers are the same as ours — multiples of five especially are conserved from their Proto-Indo-European roots, but the system as a whole is meant to roll off the tongue as a rhyme, as unforgettable as “eeny meeny miny mo.” In fact, the children’s nursery rhyme “Hickory Dickory Dock” probably has its origins from this ancient Celtic counting rhyme, via the numbers “hothera dovera dick.”

The reason the yan-tan-tethera numbers are so fun to say out loud is the same reason that epic poetry is written in rhyming meter — repetitive, rhyming lines are very easy to memorize, which is enormously important for primarily oral cultures.

This really blew my mind.

It turns out that the yan-tan-tethera counting system really was familiar to me, and probably you too — every schoolkid in America already knows it as “Hickory Dickory Dock,” though its origins as a Proto-Celtic counting system are long forgotten.

With that, I would like to conclude the bumfit-th article I have written for Maximum Effort, Minimum Reward.

When I was reading that aloud it triggered some memory I had to think about … it has a similar meter to a counting rhyme for telephone wiring - for twisted pair cable .

Blue orange green brown slate

Blue-white blue-orange blue-green blue-brown blue-slate

Orange-white orange-green orange-brown orange-slate

Green-white green-brown green-slate

Brown-white brown-slate

Slate-white

Absolutely fascinating -- a dead language that survives only in a children rhyme and to count sheep. Thanks for writing this article!